Head and Neck Cancer Foundation Sponsors Nurses for Facial Reconstruction Training: A Letter of Appreciation

Dear Associate Professor Havas and Associate Professor Meller,

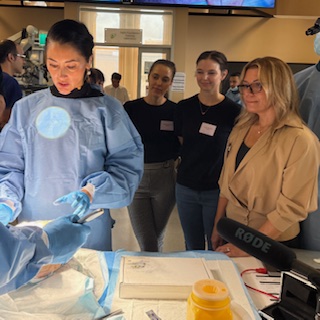

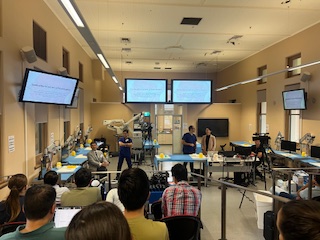

Kellie and I would like to sincerely thank the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation for sponsoring us to attend the AAFPS Facial Reconstruction and Facial Rejuvenation Dissection Course as observers on 27th March.

It was a privilege to be part of such a unique and significant workshop. We are truly grateful for your support of nursing professionals. The program was exceptionally well-organised and provided invaluable insights into both reconstructive and rejuvenation techniques.

We would also like to acknowledge the outstanding contributions of the guest speakers. Their expertise, generosity in sharing their knowledge, and the live demonstrations made for an incredibly informative experience.

Opportunities like this are especially meaningful for nurses working in rural settings, like Kellie, where access to specialised education can be limited. The Foundation’s support makes a genuine difference, particularly for those of us outside metropolitan centres.

Please find below some photos from the day.

Thank you again for this wonderful opportunity.

Warm regards,

Paula

Head and Neck Cancer Foundation Pioneers Targeted Drug Delivery to Improve Healthcare in Remote Communities

The Head and Neck Cancer Foundation supports the research of The Benignancy Group, an Australian biotech working on groundbreaking, patented mesh technologies in collaboration with the University of New South Wales’s School of Chemistry.

Chronic ear disease, particularly with perforated eardrums, is a major health issue in many rural and Indigenous communities. In these areas, access to high-quality medical care is limited. Treatments tend to be invasive, costly and difficult to manage.

Prof. Havas and A/Prof. Nguyen are working on a biodegradable mesh to place directly into the ear and treat the perforated eardrum. They say the key innovation lies not only in the implant design but also in the precise release of the therapeutic agent.

“The mesh is impregnated with a drug that encourages tissue regeneration and closes the hole in the eardrum,” A/Prof. Nguyen says. “It would be engineered to ensure that the drug is delivered in a controlled and predictable manner, to facilitate an accelerated healing – eliminating the need for surgery.”

Read the full article here.

A 2024 Snapshot: Myringomend, cancer mesh, and our ground-breaking Facial Nerve Unit

Myringomend accelerates eardrum repair

Exciting progress continues on Myringomend, a ground-breaking technology designed to repair holes in the eardrum. Supported by research from the H&NCF, Myringomend has the potential to transform how we treat eardrum injuries, offering a game-changing solution for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations across Australia.

What makes Myringomend so innovative is its ability to close eardrum holes—often without the need for general anaesthesia—in a simple office setting. This is a significant advancement, as current treatments typically require more invasive procedures in a hospital environment.

Research has now entered an exciting new phase: animal trials will begin in early 2025, with clinical trials set to follow later in the year. This marks a major step toward bringing this life-changing treatment to patients.

At H&NCF, we’re thrilled by the progress being made and are proud of the potential Myringomend holds to improve the quality of life for all Australians.

Our first cancer mesh gains momentum

The ground-breaking research into our first cancer mesh continues to make significant strides, thanks to the ongoing support from the Howarth Foundation.

In collaboration with renowned expert Professor Minas Coroneo, we are developing a specially engineered mesh that will be infused with a unique combination of molecules—discovered and patented by Professor Coroneo. This innovative mesh is set to undergo bench-top trials for specific cancers, marking a major step forward in cancer treatment.

We are excited about the progress being made and look forward to sharing the results of these trials in the second half of 2025.

The facial nerve unit expands its reach

Under the leadership of Professor Meller, the Facial Nerve Unit at the Prince of Wales Hospital continues to grow and enhance its services, supported by the ongoing generosity of the H&NCF.

The unit is at the forefront of both clinical and basic science research, contributing to ground-breaking advancements in the field. Its reach is expanding internationally, with increasing collaborations with overseas institutions and plans for additional Fellowship training opportunities.

Renowned as a centre of excellence, the Facial Nerve Unit is proud of its national and international reputation. With your continued support, we are excited to further expand our services and impact in the future.

Tracheotomy training enhances patient care

Paula Gunner continues to lead exceptional annual courses on comprehensive tracheotomy care, and the H&NCF is proud to support these vital training programs year after year.

These courses play a crucial role in improving patient outcomes by equipping healthcare professionals with the skills and knowledge needed to provide the best care for tracheotomy patients. Having navigated some of the most challenging times, we are grateful for your continued support, which helps ensure a brighter and more impactful future for both the courses and the patients they serve.

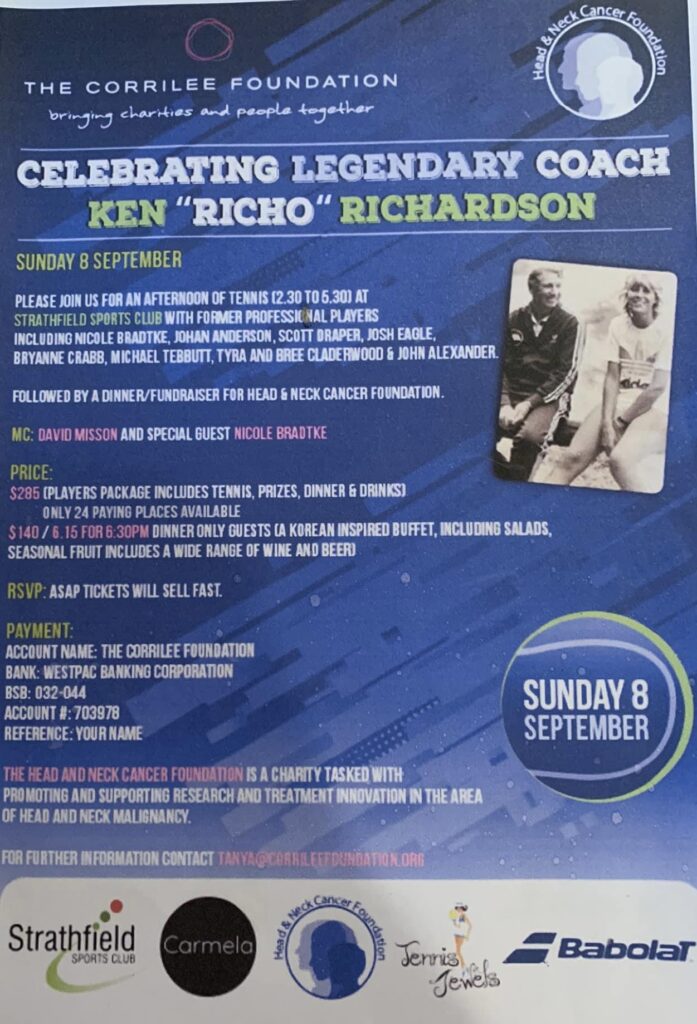

The Corrilee Foundation celebrates legendary tennis coach Ken “Richo” Richardson and donates all profits to the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation

On Sunday 8 September, the Corrilee Foundation will host an afternoon of tennis celebrating the contributions of legendary coach Ken Richardson followed by a fundraiser for the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation.

We are honoured to be a part of this important event commemorating a lifetime great in Australia’s tennis world.

The Head and Neck Cancer Foundation welcomes Doctor Shamil, our first Fellow in Facial Nerve and Facial Reconstructive Surgery at Prince of Wales Hospital

With the Foundation’s support, we welcomed our first Fellow in Facial Nerve and Facial Reconstructive Surgery at Prince of Wales Hospital. Dr Shamil, a post-graduate Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in the UK, joined our team in October 2023, and spent time furthering his skill set with Associate Professor Catherine Melor, and several other ENT and Oculoplastic Surgeons.

The Fellow in Facial Nerve/Facial Reconstruction plays a pivotal role in advancing patient care and research at the Prince of Wales Public Hospital Facial Nerve Clinic. Read the full article by the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation’s Associate Professor Catherine Melor here.

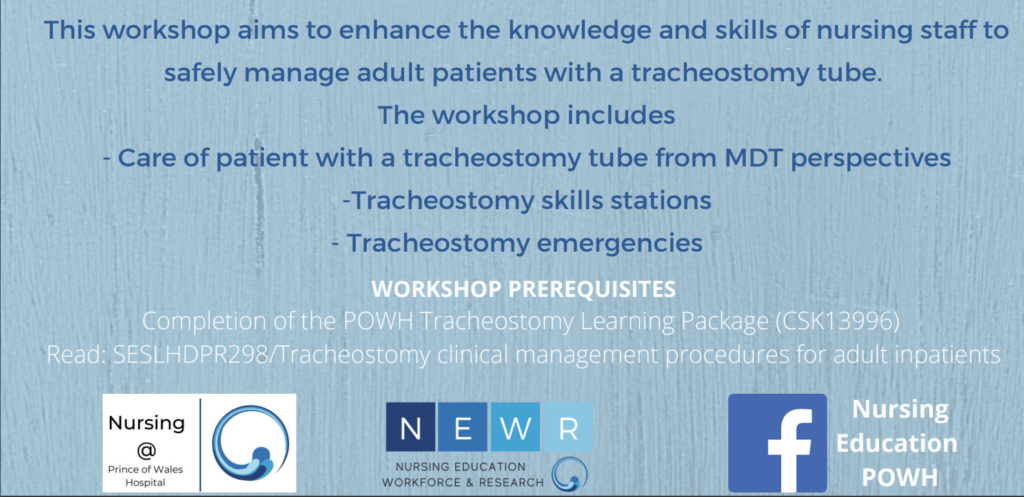

Tracheotomy Workshop at Prince of Wales Hospital to be led by board member Paula Sankey

Our board member and clinical nurse consultant Paula Sankey will be running a tracheotomy workshop at Prince of Wales Hospital on April 23, 2024, sponsored by the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation.

We must remember that nurses are the unsung heroes of head and neck cancer care. They provide the intensive medical and emotional support that people with head and neck cancers need and together with other health professionals, such as speech pathologists and physiotherapists, enable us to achieve outstanding results that we do achieve.

Please see below for a full program of the tracheotomy workshop.

The Head and Neck Cancer Foundation mentors young doctors

The Head And Neck Cancer Foundation continues to guide and mentor young doctors with their research and career development.

Please find below a recent article written by young doctors and specialists in training who are currently being mentored by Professor Havas and supported by the H&NCF.

It is an interesting collaborative study putting together a publication based on collective data from head and neck cancer units on three continents.

Your continued support of the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation guarantees ongoing funds for cutting-edge research in the causation and treatment of head and neck cancers and the introduction of innovative, novel therapies and approaches to drastically improve survivors’ quality of life.

Head and Neck Cancer Fellow 2023/2024

The Foundation is delighted to report that Doctor Eamon Shamil has been appointed the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation Fellow for 2023/2024. Doctor Shamil comes from The Royal National ENT Hospital, UCLH, in London, to undertake a second Fellowship in Facial Plastics and Reconstructive Surgery here in Sydney.

He will be working under the direction of Associate Professor Catherine Meller in the areas of diagnosing and habilitating facial nerve injuries, complex nasal and facial reconstructions, and static and dynamic rescue procedures following injuries, cancers, or major surgery that result in irreparable damage to the facial nerve.

He is delighted at the opportunity to advance his skill set in the management of complex facial reconstruction including reanimation surgery for facial paralysis, reconstruction of head and neck cancer defects, and adjunctive aesthetic procedures such as facelift and blepharoplasty.

The Head and Neck Cancer Foundation’s Rapid Access Clinic has officially launched at Princes of Wales Hospital

The Head and Neck Cancer Foundation’s Rapid Access Clinic was a ground-breaking model of early detection and free treatment for head and neck cancers that ran at Prince of Wales Hospital from 2021 to 2022.

The Head and Neck Rapid Access Clinic is a novel strategy to provide optimal head and neck cancer care. It is a free, bi-weekly service at the Prince of Wales Hospital’s Nelune Centre available to the public via a single phone call. Our mandate is to provide personalised, resource-cognisant precision medicine for our community.

Early diagnosis leads to less invasive treatments and better outcomes and this is the driving ethos of the clinic. Patients are seen by a team including a specialist and a clinical nurse consultant and are either triaged for expedited treatment or placed on a surveillance database.

The team has already reviewed 28 patients who presented with concern for head and neck cancer. Of these, 21% were diagnosed with cancer. The clinic is drastically reducing the delay between seeing a GP and receiving treatment from the gold standard of 62 days to an approximate delay of only 24 days.

The Rapid Access Clinic is also developing an interacting app for both clinicians and patients. It will improve healthcare literacy by quantifying concerning symptoms and notifying patients and clinicians in ‘real-time’ of any functional, pain, or mental health issues for review.

Workshops in Tracheotomy Care are coming to Prince of Wales Hospital

Our clinical nurse consultant Paula, an important member of the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation, is running these free tracheotomy training courses as part of our ongoing commitment to education.

Rapid Access Clinic to launch at Prince of Wales Hospital

After significant lobbying by the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation, a clinical trial of the Rapid Access Clinic for patients with possible head and neck cancers is to be established at the Prince of Wales Hospital. $150,000 has been allocated to run this clinical trial over the next 18 months.

We are very excited by the prospect of providing a novel portal of entry for patients with symptoms including hoarseness of voice, difficulty swallowing and any lump on the tongue, mouth, or neck. Risk factors such as smoking, vaping or family history will also be considered to assess potential patients who are reasonably worried about having an early-stage head and neck cancer.

Direct entry into the clinic will be facilitated by one phone call to the head and neck cancer/translational medicine fellow.

Contact details are being finalised and we will update these early next month.

Chasing Clouds

A five-part podcast series exploring the social and public health impact of vaping in contemporary Australia

This engaging, evidence-based podcast series draws upon the expertise of young people, doctors, educators, vapers, academics, and frontline community organisations to bring to light key social and public health issues around e-cigarettes and what we can do moving forward.

What are the health impacts of nicotine and non-nicotine vapes?

How common is vaping amongst Australian youth and how are e-cigarettes being aggressively marketed to them on social media?

What are the arguments for using e-cigarettes as a tool to quit smoking for adult smokers who have tried everything else?

What kind of regulation is necessary to ensure e-cigarettes become inaccessible to teenagers?

What is working in existing Australian education programs and what isn’t working?

How can vaping rates be most effectively reduced among Australian young people?

These are some of the questions asked in this podcast series.

Listen to this podcast series on YouTube here or on Apple Podcasts here.

Chasing Clouds is a QUO podcast series produced in collaboration with the Prince of Wales Hospital Foundation and the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation.

World Head and Neck Cancer Day 2021

Today is World Head and Neck Cancer Day, an auspicious day where we celebrate survivors of head and neck cancer and commemorate those who have not been so lucky. This is an opportunity for all of us to raise awareness of the importance of education, early presentation, screening, and ground-breaking research.

Education

It is essential for the general public to understand the initial symptoms of head and neck cancers. Given how complex and varied this group of cancers is, symptoms can range from a change in voice, difficulty swallowing, or a lump in the mouth, tongue, or neck.

Early Presentation

We need to start reminding ourselves, our family, and our friends of the importance of not denying early symptoms. Reaching out to a health professional may seem daunting, but it will arm you with either peace of mind or an early start to your treatment journey. Early presentation leads to minimal intervention, improved outcomes, and better quality of life.

Screening

There is currently no regular screening program for head and neck cancers in Australia. However, this is soon to change given the imminent launch of our very own Rapid Access Clinic, which will allow anyone at high risk of head and neck cancers to be seen at Prince of Wales Hospital by an expert in real-time; either on the same day or the next day.

Research

Australia has seen a 34% increase in head and neck cancer in the last 10 years with over 5,000 people diagnosed every year.

Our multi-disciplinary approach to research has led to an ongoing collaboration between medical and biomedical engineering teams. We are particularly focused upon HPV-related head and neck cancer research as we pioneer novel interventions that will improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

Help us to continue educating and encouraging early access to health care for high-risk populations and innovative, patient-centric research by making a donation today.

From thyroid cancer at 25 to motherhood

From the outside, 34-year-old Katrina Mae is an accomplished young woman who has managed to strike a perfect balance between work and family. She is a Special Counsel at a top commercial Australian law firm and has a healthy 6-month-old daughter, Amelia. Katrina is also a survivor of papillary thyroid carcinoma, the most common form of thyroid cancer and one that primarily affects younger people. We interviewed Katrina about her head and neck cancer survival journey and how it is has changed her.

Can you tell me about the circumstances surrounding your initial diagnosis?

I received my diagnosis in 2012 when I was 25. I had just gotten engaged, was planning my wedding and my fiancé was away overseas so you can imagine that it was rather dramatic timing. My symptoms began as a sore throat with a little lump. I told my mum and sister who said it’s probably nothing serious but that I should still get it checked out. So I went to the local doctor who said it’s probably just a nodule on the thyroid. They did a biopsy which came as a surprise to me; I thought it would be a swab or something less invasive, but they were sticking needles into my neck while I was awake. If it came back benign, I would have just needed some thyroid medication. My father had had some thyroid issues previously so I assumed it just ran in the family. My doctor then told to see the specialist ENT surgeon Professor Jonathon Clark. When I arrived, he told me that I had papillary thyroid carcinoma (thyroid cancer) and that it may be in my lymph nodes and neck as well. He said he would need to do more biopsies to work out the scope but that I would definitely need surgery.

As a young woman, any type of cancer is not something that one necessarily has on their radar. How did this diagnosis impact you on a personal level?

It was a terrible shock. I went to my appointment with Professor Clark thinking that I’d only be getting some medication. My parents had actually offered to come with me to the appointment because my fiancé was away, and I had said there was no need and that I could go by myself. When I got out, I was overwhelmed and distraught. I immediately rang my parents and told them what had happened. I had actually planned to go out for dinner with some friends afterward as I was so confident I would be fine. I went to that dinner and told my friends that while I have cancer and I’m worried about whether I’m going to live, everything is fine. It was a bit of a denial for a while. It wasn’t until I actually spoke to my fiancé later that night when he rang me from East Timor that it hit home. His reaction prompted my reaction, and I finally recognised that it was very serious and poor timing with my other half out of the country. I’m lucky that I have a good family around who looked after me. I think the medical team that subsequently took me through my surgery and treatment was also phenomenal so I can’t complain.

What did your treatment involve?

I had a radical neck dissection where they removed my thyroid and 159 of my lymph nodes, and I was then treated with radioactive iodine. They also had to remove a small part of my thyroarytenoid muscles which is the muscle that sits next to the voice box, as the cancer was growing into that. I had all my surgery out of St George Private Hospital but then about 8 weeks after I’d had the surgery, I went into St George Public Hospital to their oncology unit for the radioactive iodine which involved swallowing a pill that kills cancerous cells while leaving other body cells relatively unharmed. Part of the thyroid’s job in the body is to absorb iodine so it essentially tricks any cancerous thyroid tissue that is left in the body after surgery into sucking up the radiation. They had already removed most of the cancer but if there was anything else floating around my body, they were then able to kill that off with the radioactive iodine treatment. At the end of the treatment, they scanned me to check how much radiation I was emitting which was still only a low frequency. The fact that there was nothing or not much showing up was indicative of the fact that there hadn’t been much left behind by the surgery which gave me quite a bit of reassurance.

Did your treatment affect your voice production?

I saw a speech therapist at St George Public Hospital for a handful of sessions. With the nature of my work as a lawyer, I do a lot of speaking and my voice was getting tired very quickly which affected my projection. I actually didn’t realise it would be a possible side effect before the surgery. The doctors came in while I was in ICU afterwards, asked if I could talk, and then inspected my voice box and throat. I was very lucky that it didn’t affect me severely. After a couple of speech pathology sessions, all I needed to do was put into action the things that they taught me in those sessions.

Did you have access to any peer support services during your recovery?

I haven’t connected with anyone else who’s had head and neck cancer at all. On a few occasions, I’ve been interested to meet either colleagues, clients, and friends down the track who had other types of cancer when they were quite young. We bonded over those experiences to a degree. I actually haven’t even met anybody else who’s had head and neck cancer at all, let alone in my age group. I feel like it’s something that is rarely talked about.

Did you want more patient support during your treatment and subsequent recovery?

I had the support I needed but I was very lucky in that my surgery and treatment were effective the first time around. It was a fairly rough three months, but it was only a three to four-month period that I was having surgery, recovering, and undergoing treatment. This is a relatively short period as compared to people who might have another form of head and neck cancer and need multiple surgeries or multiple rounds of treatment. That said, I can imagine it would be very helpful to speak to other people who have already recovered. That way, you can gauge what are you in for and see a light at the end of the tunnel. I always think that makes you feel better knowing that people feel better with time

Did having thyroid cancer mean certain milestones were delayed for you?

I had to wait at least 12 months to become pregnant after the initial treatment. About three years in, when I went back for some more radioactive iodine for scanning purposes, I again had to wait a further year to conceive. So all up I had to wait four years after the surgery. The other factor is that iodine is quite important for the development of a baby so they have to monitor your medication quite closely before you decide to have a baby, once you’ve had your thyroid removed. Given that I’ve now got my healthy little baby Amelia with me, it all seems worth it.

How do you feel changed by your experience of thyroid cancer?

I grew up being a very gentle, timid kind of person and I was always terrified by medical procedures. I really had to toughen up. It does build resilience. As my mum said to me subsequently, I think about the things that I have gotten through in life and if I can get through that, I can get through anything. The silver lining was that it showed me that I was made of a bit more than I thought in terms of my personal strength.

I am now nine years since my initial diagnosis and remain cancer-free. It was such a scary time, so I would love to do anything to help others facing the prospect of a head and neck cancer diagnosis. Beyond this, I want to support research to find targeted ways to remove all types of cancers that don’t injure the host as much as traditional chemo or radiotherapy.

Reflections of a senior paediatric and adult head and neck surgeon

We interviewed Doctor Ian Jacobson, a senior paediatric and adult head and neck surgeon at Prince of Wales hospital with a particular interest in paediatric otolaryngology and head and neck oncology. As a member of the board of directors at the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation, he believes that self-reflection and research is imperative in any profession, but all the more so in the medical sphere.

From your perspective as a senior ENT surgeon, why do you think research into head and neck cancer is important?

Unless we constantly re-evaluate what we do, we do not learn from our previous misconceptions. When I was a young doctor, surgical treatments were often based on opinion and dogma. Fortunately, during my practising lifetime that has changed substantially.

What kinds of gains do you think need to be made in the field of paediatric otolaryngology to improve the lives of children suffering from ENT problems?

We need evidence. Data derived from large studies or metanalysis of previous research is increasingly providing guidance on appropriate treatment options. International, evidence-based treatment paradigms are emerging for many of the common conditions in paediatric ear nose and throat surgery. It is incredibly useful to be able to say to a parent, “based on specific research, or a well-researched international guideline the right treatment for your child is as follows…!”

How do you think the research the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation supports can make a tangible positive impact on clinical outcomes for your patients?

Australia has a rich tradition of research in Otolaryngology Head and Neck surgery and our research group has contributed significantly to that in the last few years. Our group is currently investigating a number of innovative treatments of direct application to several diseases in the head and neck region. The early work is promising, and we hope it will translate to improving the delivery of healthcare to millions of people worldwide.

What initiative of the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation are you most excited about and why?

Our monthly research meeting is an inspiring experience. Imagine a group of individuals spanning all stages of their medical career from student to senior members perhaps at the twilight of their career meeting in an egalitarian setting. You have the combination of several decades of clinical and academic experience together with youthful vigour and a thirst for new knowledge. It is inspiring to see our medical students and junior postgraduate doctors take hold of an idea and run with it while their peers and senior members at the meeting provide guidance. It truly is an exciting meeting each time.

What do you hope the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation grows into in the next five years?

The Head and Neck Cancer Foundation has grown from a standing start significantly in the last three years. I am hoping that the Head and Neck research group will grow both in numbers and in reach. I envisage biomedical engineers, basic scientists, members of the allied health medical professions and ethicists all participating in research under the umbrella of the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation. Some of our members have already collaborated with research groups overseas and interstate. We are hoping that will continue to grow.

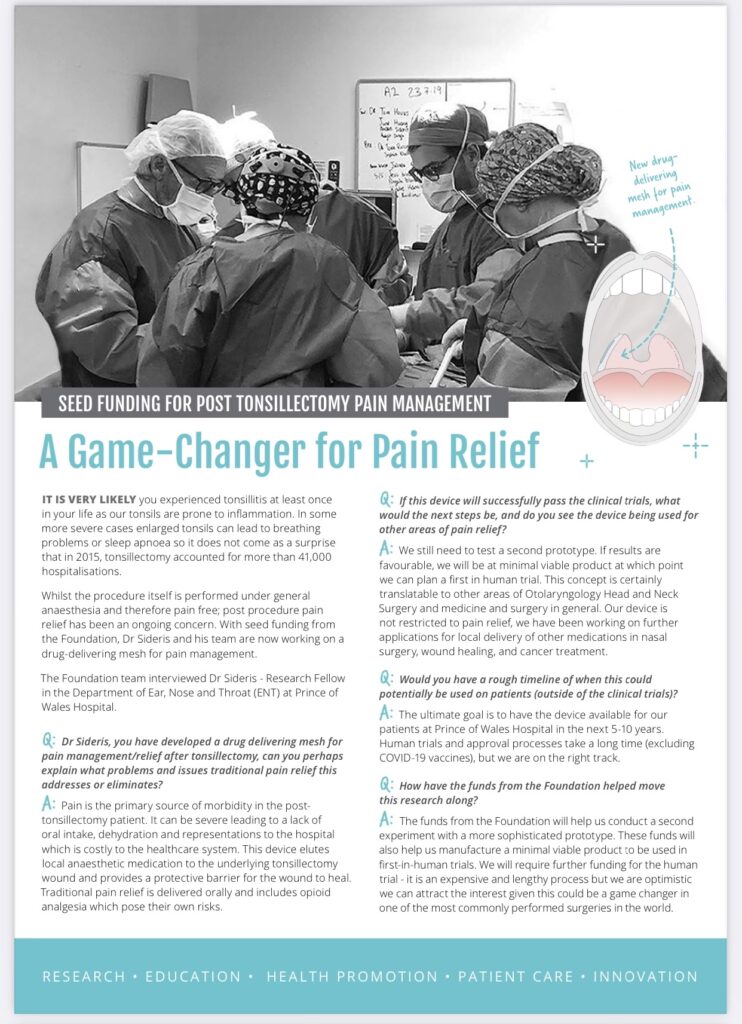

A game-changer for pain relief

Dr Anders Sederis (our 2019 grant recipient) recently completed his masters thesis in a biodegradable novel mesh impregnated with nanoparticles to prevent pain and optimise healing after tonsillectomy.

This project is part of a group of research projects directed by Professor Havas in the development of novel technologies to treat and improve the quality of life not only of patients with head and neck cancers but also patients undergoing necessary common operations.

The Prince of Wales Hospital Foundation has very generously provided seeding capital for this project to go to second-stage animal studies. We are optimistic of being in a position to commence clinical trials mid to late-2022.

Doctor Catherine Meller on the importance of head and neck cancer visibility and work-life balance

This week, we interviewed Head and Neck Cancer Foundation co-director Doctor Catherine Meller. Learn more about how she balances being an Otolaryngologist and facial reconstructive surgeon as well a mother of three as she passionately advocates for increased visibility and funding for head and neck cancer research in Australia.

What motivated you to get involved with the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation?

I’ve always enjoyed the charitable aspects of working in healthcare, and then a great opportunity presented itself to become part of something that I feel is a very under-resourced area in medicine. For many years, enthusiastic young doctors have come through the system with wonderful ideas but very few resources to enable them. The prospect of raising funds to allow brilliant young minds to research and extend the boundaries of what we know about head and neck cancer is a very worthwhile cause that I have jumped at the opportunity to be a part of.

Why do you think Head and Neck Cancer research needs more visibility and funding in Australia?

Head and neck cancers makes up about five percent of all cancers in Australia, but it is a very disfiguring disease that impacts upon our ability to speak breathe or eat properly. As a facial plastics and reconstructive surgeon, I get to see first-hand how life saving surgery and other treatments for cancer can have lasting negative psychological impacts on the patient. Patients are often distressed about their inability to enjoy a meal, or very self-conscious about how their face may look after surgery or radiotherapy. This can often lead to them withdrawing from society and experiencing extreme isolation and loneliness. Ultimately, the terrible impact that head and neck cancer can have on many people is sometimes rendered invisible because of this. I believe it is our responsibility to raise awareness and funding in a meaningful way for a group of patients who so desperately need it.

What has your experience been as a woman in the highly male-dominated world of ENT surgery?

Interesting! I’m really pleased to report that there are more women joining the ranks as they come through training. That said, when I was training myself, I only came into contact with two female ENT surgeons over my five years of training in nine different hospitals in New South Wales. I didn’t really have a role model in an ENT female surgeon per se, but what I did have (and now fully appreciate the significance of) were male champions. These are colleagues who promote fairness, equality, and are willing to stand up for female surgeons in a male dominated field. In fact, I was actively encouraged to join Prince of Wales to contribute a different perspective and have my own voice in what was, prior to my appointment, an entirely male department. The world of surgery is becoming an increasingly diverse place, and it is an exciting time to be a part of it.

How do you maintain a work-life balance as a successful ENT surgeon and mother?

This is one of the most difficult questions I have to answer regularly. I don’t think I’ll ever get it quite right, but that is because I love my family and I am also extremely passionate about my job. There are different parts of me that feel fulfilled by each of these roles, and I try to take it week by week. The thing about young kids is that life is often quite unpredictable and can change daily – as in what they need from you as a parent. Ultimately that comes first, but the truth is that I wouldn’t be able to enjoy my career without having a lot of family support. I’m very privileged to enjoy that position, and having regular pulse checks on the state of our household between me and my husband, who is doing what and going where, is also very helpful!

What advice/words of wisdom would you give young women wanting to get involved in ENT surgery?

It’s a wonderful field, and a very rewarding career. I would encourage anyone to go for it as soon as you know that it is truly what you want to do. I always get asked questions like, “but when is it a good time to have kids“, or “but what about if I want to get married and take some time off?“. My experience is this – there will always be reasons not to pursue a career in surgery. It is very difficult on both you and your support network. It is also exhausting, both emotionally and financially. Only you will know whether it is truly worth it.

If you’ve made the decision to commit yourself to a career in surgery, then I promise you, everything else can be worked out. Not without sacrifice and determination mind you, but it can be done.

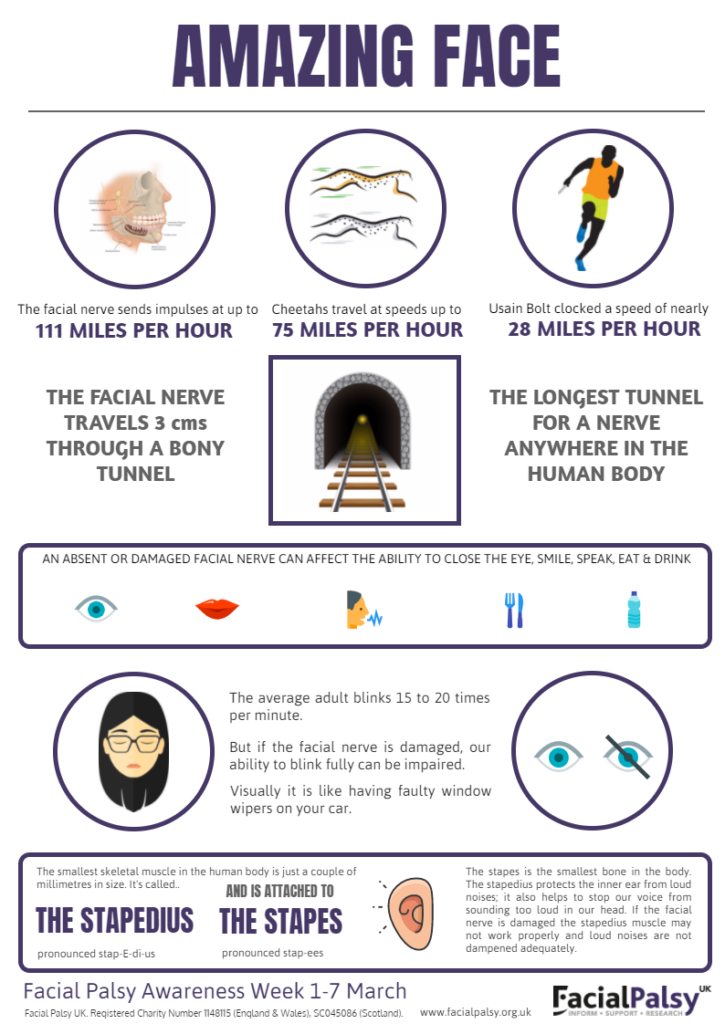

Facial Palsy Awareness Week

In honour of Facial Palsy Awareness Week from March 1 to March 7, we interviewed facial palsy specialist and member of the board of the Head and Neck Foundation, Doctor Catherine Meller.

What is facial palsy?

Facial palsy (FP) generally refers to weakness of the facial muscles, mainly resulting from temporary or permanent damage to the facial nerve.

When a facial nerve is either non-functioning or missing, the muscles in the face do not receive the necessary signals to allow them to function properly. This results in paralysis of the affected part of the face, which can affect the movement of the eye(s) and/or the mouth, as well as other areas.

Although the most commonly known cause of facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy, there are actually many different causes of facial palsy, and treatment and prognosis vary greatly depending on the cause.

What are the symptoms of Facial Palsy (FP)?

Facial palsy causes many physical problems, including asymmetry of the face, problems closing the eye, difficulty eating and drinking, and trouble with speaking clearly.

It also has devastating emotional effects. Patients lose the ability to smile and are often perceived as ‘negative’ or ‘angry’. Patients with FP may have trouble displaying emotion, causing miscommunication and self-consciousness. Patients frequently suffer from anxiety and depression as a result of the functional and cosmetic aspects of FP.

What is the Prince of Wales Facial Nerve and Facial Reconstruction Clinic?

I founded the Prince of Wales Facial Nerve Clinic in 2018 because I am passionate about rehabilitating and treating patients with facial nerve injuries. The clinic is the only one of its kind in NSW and includes real-time diagnostic nerve tests thanks to an ENoG machine donated through the Prince of Wales Hospital Foundation. It allows us to rapidly diagnose nerve injuries, and begin treatment straight away to give patients the best possible chance of regaining full function of their nerve.

For patients who suffer from permanent nerve injury, we offer on-the-spot Facial Nerve Physiotherapy, hearing tests, counselling services, botox treatment for muscle spasms and synkinesis, and speech therapy. Some patients may benefit from surgery to ‘reanimate’ the face, using donor nerves and/or muscles, and these are performed at Prince of Wales Hospital using cutting-edge techniques and technology.

Thalia’s Story

When Thalia was 19 years old, she became very unwell with a weakness of her muscles that rapidly spread throughout her body. She was rushed to the hospital and cared for in ICU, and diagnosed with Guillan Barre Syndrome.

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is a condition affecting the nerves that control our senses and movements (peripheral nerves) including the facial nerve. They leave the brain and spinal cord and carry impulses to and from the rest of the body.

The cause of GBS is unclear. Normally when we develop an infection, the body’s natural defense system produces “antibodies” which attack and kill viruses and bacteria. GBS causes this natural defense system to become out of control, and antibodies start to attack the body itself, specifically, the protective covering of the nerves. Once this is damaged, the nerve can no longer send signals to your muscles or organs to enable them to perform the jobs they normally carry out.

Over a period of many weeks, most of Thalia’s nerves recovered. Unfortunately, her facial nerves to both sides of her face were left weakened, and despite physiotherapy, Thalia has been left with an impaired ability to show emotion, in particular, positive emotions including smiling and laughing.

Thalia was referred to the Prince of Wales Facial Nerve Clinic by her neurologist. She has recently undergone a procedure to improve her ability to smile, by using another nerve (one that controls the muscles that help us chew) to ‘supercharge’ the weakened facial nerve. She is in the process of training her brain to use this nerve to power her smile, through specialised physiotherapy. Thalia is passionate about raising awareness of this condition and is currently completing tertiary university studies in the field of forensic sciences.

Why is Facial Palsy Week important?

Facial Palsy (FP) can significantly impact a patient’s psychological as well as physiological health. Facial expressions are a crucial way of relating to the world, and when one’s ability to express themselves in line with how one is feeling is taken away, it can lead to a lack of social connection, social isolation, anxiety, and depression. The Prince of Wales’ Facial Nerve and Facial Reconstruction Clinic helps patients regain control of their facial expressions and empowers them to reconnect with others in this essential but too often forgotten way.

Fordham School of Translational Medicine

Our multi-disciplinary, problem solving-focused vision: A school of translational medicine in Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery

The traditional definition of translation medicine focuses on translating medical advances from the laboratory to bedside. However, at the Head and Neck Cancer Foundation, we have a different vision that begins by identifying a clinical need.

“We’re all about looking after patients, treating clinical conditions, getting some insight into where we’re providing good treatment, and understanding where we’re not, so we can work backward to fill a need,” says Professor Thomas Havas.

Although Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery is far from the glamour areas of science research, approximately every third visit to a General Practitioner is for an ENT-related issue. There is huge prevalence with massive community cost and treatments are often more profit-focused than problem-focused.

Professor Havas explains a practical application of this.

“About ten years ago, it started to become popular to wash your nose out with saltwater spray. There’s no good evidence that it achieves anything and yet last year in America, Americans spent over $2000 million buying saltwater to wash their nose out with. It’s not science-based but profit-based and it’s usually the manufacturers of the saltwater spray who hire a couple of prominent Otolaryngologists with a significant financial incentive to spruik a product with little evidence backing it up,” he says.

The future School of Translational Medicine in Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery will focus on science-driven solutions to clinical needs as opposed to the current framework that is too often fear and economically driven. We will create an independent school with academic credibility, staffed by senior Otolaryngologists and researchers who appreciate that the hackneyed commercially-driven approach is no longer appropriate.

“The school will provide a grassroots approach ranging from common problems to innovative treatments for Head and Neck Cancer. It will be holistic and ecumenical, focused primarily on improving patient outcomes,” explains Professor Havas.

Another unique aspect of our school will be controlling the commercialisation process. While profit from medical advances is important, it needs to be reframed to become more eco-friendly. This means that a significant amount of profit will not only go to the individuals who own the intellectual property but will be used to support universities and to a lesser extent, hospitals.

“You don’t have to make obscene profits to make medical advances profitable.”

The Head and Neck Cancer Foundation Research Group is already engaging in a multi-disciplinary approach to research. We have been collaborating with biomedical engineers and other scientists for the last three years as evidenced by our research reports.

“What strikes me is that hitherto and in many other areas, how little interaction there is between biomedical engineers and clinicians generally. We bought half a dozen of these students into the operating room and they have never been in an operating room. They are intelligent, they have enormous skill bases that we as clinicians don’t have, but there has been no integrated vision or foresight in terms of bringing the two together,” says Professor Havas.

The School of Translational Medicine will be unique worldwide in its multidisciplinary, inter-disciplinary, problem-focused, and product development-focused approach. As a clinician-led school, it will also include basic scientists, biomedical engineers, and lawyers to teach students about both intellectual property and the commercialisation process.

“The quicker we can bring to market, the quicker it is at the bedside, and the quicker patients benefit,” says Professor Havas.